Lecture 12 — Controlling Loops¶

Overview¶

- We will see how to control both for and while loops with

- break, continue

- We will see different range functions

- We will write many example programs

Reading: Practical Programming, rest of Chapter 7.

Part 1: The Basics¶

- for loops tend to have a fixed number of iterations computed at the start of the loop

- while loops tend to have an indefinite termination, determined by the conditions of the data

- Most Python for loops are easily rewritten as while loops,

but not vice-versa.

- In other programming languages, for and while are almost interchangeable, at least in principle.

Part 1: Ranges¶

We already started using ranges in last lecture, but we will go over them in detail here.

A range is a function to generate a list of integers. For example,

>>> range(10) [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Notice this is up through and not including the last value specified!

If we want to start with something other than 0, we provide the starting values

>>> range(3,8) [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

We can create increments. For example,

>>> range(4,20,3) [4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19]

starts at 4, increments by 3, stops when 20 is reached or surpassed.

We can create backwards increments

>>> range(-1, -10, -1) [-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7, -8, -9]

Using Ranges in For Loops¶

We can use the range to generate the list of values in a for loop. Our first example is printing the contents of the planets list

planets = [ 'Mercury', 'Venus', 'Earth', 'Mars', 'Jupiter', 'Saturn', 'Uranus', 'Neptune', 'Pluto' ] for i in range(len(planets)): print planets[i]

The variable i is variously known as the “index” or the “loop index variable” or the “subscript”.

We will modify the loop in class to do the following:

- Print the indices of the planets (starting at 1!)

- Print the planets backward.

- Print every other planet.

Loops That Do Not Iterate Over All Indices¶

Sometimes the loop index should not go over the entire range of indices, and we need to think about where to stop it “early”, as the next two examples show.

Example: Returning to our example from Lecture 1, we will briefly re-examine our solution to the following problem: Given a string, how can we write a function that decides if it has three consecutive double letters?

def has_three_doubles(s): for i in range(0, len(s)-5): if s[i] == s[i+1] and s[i+2] == s[i+3] and s[i+4] == s[i+5]: return True return False

We have to think carefully about where to start our looping and where to stop!

Part 1 Exercises¶

Generate a range for the positive integers less than 100. Use this to calculate the sum of these values, with and without a for loop.

Use a range and a for loop to print the even numbers less than a given integer n.

Suppose we want a list of the squares of the digits 0..9. The following does NOT work

squares = range(10) for s in squares: s = s*s

Why not? Write a different for loop that uses indexing into the squares list to accomplish our goal.

The following code for finding out if a word has two consecutive double letters is wrong. Why? When, specifically, does it fail?

def has_two_doubles(s): for i in range(0, len(s)-5): if s[i] == s[i+1] and s[i+2] == s[i+3]: return True return False

A local maximum, or peak, in a list is a value that is larger than the values next to it. For example,

L = [ 10, 3, 4, 9, 19, 12, 15, 18, 15, 11, 14 ]

has local maxima at indices 4 and 7. (Note that the beginning and end values are not considered local maxima.) Write code to print the index and the value of each local maximum.

Part 2: Nested Loops¶

Some problems require “iterating” over either

- two dimensions of data, or

- all pairs of values from a list

As an example, here is code to print all of the products of digits:

digits = range(10) for i in digits: for j in digits: print "%d x %d = %d" %(i,j,i*j)

How does this work?

- for each value of i — the variable in the first, or “outer”, loop,

- Python executes the entire second, or “inner”, loop

We will look at finding the two closest points in a list.

Example: Finding the Two Closest Points¶

Suppose we are given a list of point locations in two dimensions, where each point is a tuple. For example,

points = [ (1,5), (13.5, 9), (10, 5), (8, 2), (16,3) ]

Our problem is to find the two points that are closest to each other.

The natural idea is to compute the distance between any two points and find the minimum.

- We can do this with and without using a list of distances.

We will work through the approach to this and post the result on the Piazza site.

Exercise: Nested vs. Sequential Loops¶

The following simple exercise will help you understand loops better. Show the output of each of the following pairs of for loops. The first two pairs are nested loops, and the third pair is formed by consecutive, or “sequential”, loops.

# Version 1 sum = 0 for i in range(10): for j in range(10): sum += 1 print sum

# Version 2 sum = 0 for i in range(10): for j in range(i+1,10): sum += 1 print sum

# Version 3 sum = 0 for i in range(10): sum += 1 for j in range(10): sum += 1 print sum

Exercise: Modifying Images¶

- It is possible to access the individual pixels in an image as a two

dimensional array. This is similar to a list of lists, but is written slightly differently: we use pix[i,j] instead of pix[i][j] to access a point at location (i,j) of the image.

Here is a code that copies one image to another, pixel by pixel.

im = Image.open("bolt.jpg") w,h = im.size newim = Image.new("RGB", (w,h), "white") pix = im.load() ## creates an array of pixels that can be modified newpix = newim.load() ## creates an array of pixels that can be modified for i in range(0,w): for j in range(0,h): newpix[i,j] = pix[i,j] newim.show()

Modify the above code so that:

- The image is flipped left to right

- The image is flipped top to bottom

- You introduce a black line of size 10 pixels in the middle of the image horizontally and vertically.

- Now, scramble the image by shifting the four quadrants of the image clockwise.

If you want some additional challenge, try these:

- Pixellate the image, but taking any block of 8 pixels and replacing all the pixels by their average r,g,b value.

Part 3: Controlling Execution of Loops¶

- We can control while loops through use of

- break

- continue

- We need to be careful to avoid infinite loops

Using a Break¶

We can terminate a loop immediately upon seeing the 0 using Python’s break:

sum = 0 while True: x = int( raw_input("Enter an integer to add (0 to end) ==> ")) if x == 0: break sum += x print sum

- break sends the flow of control immediately to the first line of code

outside the current loop, and

The while condition of True essentially means that the only way to stop the loop is when the condition that triggers the break is met.

Continue: Skipping the Rest of a Loop¶

Suppose we want to skip over negative entries in a list. We can do this by telling Python to continue when it sees a blank line:

for item in mylist: if item < 0: continue print item

When it sees continue, Python immediate goes back to the while condition and re-evaluates it, skipping the rest of the loop.

Any while loop that uses break or continue can be rewritten without either of these.

- Therefore, we choose to use them only if they make our code clearer.

- A loop with more than one continue or more than one break is often unclear!

This particular example is probably better without the continue.

- Usually when we use continue the rest of the loop would be much longer, with the condition that triggers the continue tested right at the time.

Infinite Loops and Other Errors¶

One important danger with while loops is that they may not stop!

For example, it is possible that the following code runs “forever”. How?

n = int(raw_input("Enter a positive integer ==> ")) sum = 0 i = 0 while i != n: sum += i i += 1 print 'Sum is', sum

How might we find such an error?

- Careful reading of the code

- Insert print statements

- Use the Wing IDE debugger.

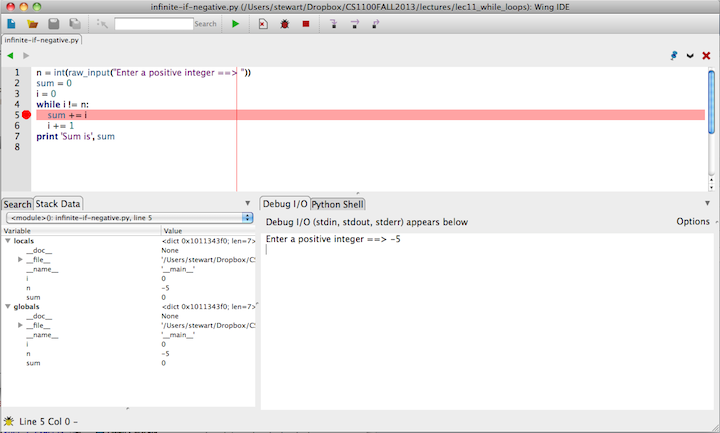

We will practice with the Wing IDE debugger in class, using it to understand the behavior of the program. We will explain the following picture

and note the use of

- The hand, bug and stop symbols on the top of the display, and

- The Debug I/O and Stack Data at the bottom of the display.

Part 3 Exercises¶

Given two lists L1 and L2 measuring the daily weights (floats) of two rats write a while loop to find the first day that the weight of rat 1 is greater than that of rat 2.

Do either of the following examples cause an infinite loop?

import math x = float(raw_input("Enter a positive number -> ")) while x > 1: x = math.sqrt(x) print x

import math x = float(raw_input("Enter a positive number -> ")) while x >= 1: x = math.sqrt(x) print x

Example: Random Walk¶

Many numerical simulations, including many video games involve random events.

Python includes a module to generate numbers at random. In particular,

import random # Print three numbers randomly generated between 0 and 1. print random.random() print random.random() print random.random() # Print a random integer in the range 0..5 print random.randint(0,5) print random.randint(0,5) print random.randint(0,5)

We’d like to use this to simulate a “random walk”:

- Hypothetically, a (very drunk) person takes a step to the left or a step to the right, completely at random (equally likely to go left or right), in one time unit.

- If the person is on a platform with

steps and the person

starts in the middle, this process is repeated until s/he falls

off (reaches step 0 or step

steps and the person

starts in the middle, this process is repeated until s/he falls

off (reaches step 0 or step  )

) - How long does this take?

Many variations on this problem appear in physical simulations.

We can simulate a steps in two ways:

- If random.random() returns a value less than 0.5 step to the left; otherwise step to the right.

- If random.randint(0,1) returns 0 then step left; otherwise, step right.

We’ll write the code in class, starting from the following:

import random # Print the output def print_platform( iteration, location, width ): before = location-1 after = width-location platform = '_'*before + 'X' + '_'*after print "%4d: %s" %(iteration,platform), raw_input( ' <enter>') # wait for an <enter> before the next step ####################################################################### if __name__ == "__main__" # Get the width of the platform n = int( raw_input("Input width of the platform ==> ") )

Summary¶

- range is used to generate a list of indices in a for loop.

- At each iteration of a for loop, a value from a list copied to a variable automatically. Do not change this value yourself.

- While loops are needed especially when the termination conditions must be determined during the loop’s computation.

- Both for loops and while loops may be controlled using break and continue, but don’t overuse these.

- While loops may become “infinite”

- Use a debugger to understand the behavior of your program and to find errors.