Logic for Relational Databases and Relational Algebra for Bags¶

In this lecture, we will talk about the relationship between relational algebra, logic and real relational database implementations.

- Database queries have a solid foundation in logic. We will first explore the relationship.

- Relational databases do implement relational algebra, but

with some differences.

- Relational databases implement bag semantics.

- We will also see some advanced operations that do not have logical correspondances but map to very useful SQL queries.

Logic and Databases¶

Relational data model is a logical model.

A set of tuples can be considered a set of facts.

Schema: heroes(hid, hero, realname) movies(mid, moviename) heroinmovie(hid, mid) Facts: heroes(1, 'Captain America', 'Steve Rogers') heroes(2, 'Iron Man', 'Tony Stark') heroes(15, 'Jessica Jones', 'Jessica Jones') movies(1, 'Captain America: The First Avenger') movies(2, 'Iron Man') movies(6, 'The Avengers') heroinmovie(1,1) heroinmovie(2,2) heroinmovie(1,6) heroinmovie(2,6)

This part of the database is considered the extensional part. What is true about this data model at this time.

Each query is considered a logic program that returns a new set of facts, derived from the extensional database. You can consider the queries defining new relations.

inavengers(X,Z) :- hero(X,_,_), movie(Y, 'The Avengers'), heroinmovie(X,Y). inmorethanonemovie(X,Y,Z) :- hero(X,Y,Z), heroinmovie(X,Y1), heroinmovie(X,Y2), Y1 <> Y2.

This type of logic used for queries called Datalog.

- Datalog is similar to Prolog, but it does not have functions in predicates (no inavengers( f(X) )!).

- Also, no cut or fail!

We can read this as:

hero(X,Y,Z)

is true for all instances of (X,Y,Z) that correspond to a tuple in the hero relation.

Datalog vs Relational Algebra¶

Any query written by relational algebra can be represented using Datalog.

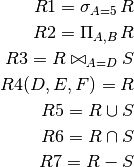

Relational algebra (assume R(A,B,C) and S(D,E,F) are given):

Let’s write the same queries using logic:

R1(A,B,C) :- R(A,B,C), A=5 R2(A,B) :- R(A,B,_) R3(A,B,C,D,E,F) :- R(A,B,C), S(D,E,F), A=D R4(D,E,F) :- R(A,B,C) R5(A,B,C) :- R(A,B,C) R5(A,B,C) :- S(D,E,F) R6(A,B,C) :- R(A,B,C), S(A,B,C) R7(A,B,C) :- R(A,B,C), NOT S(A,B,C)

Negation¶

Negation, NOT, is defined using closed-world semantics. For constants a,b,c

NOT S(a,b,c)

is true if there is no such tuple in S. The negation is not defined for a predicate with variables!

Negation has to be “safe”:

- If every every variable that appears in a negated atom of the form: NOT S also appears in a positive safe predicate in the same statement, then the negation is considered safe.

- All predicates corresponding to database predicates are considered safe. If all the rules defining a new predicate P are safe, then P is also considered safe.

Recursion¶

Note that you can write recursive queries in Datalog, but not in relational algebra.

sameuniverse(X,Y) :- hero(X,_,_), hero(Y,_,_), X<>Y, heroinmovie(X,Z), heroinmovie(Y,Z). sameuniverse(X,Y) :- sameuniverse(X,Z), sameuniverse(Z,Y), X<>Y.

- SQL contains recursion too, but it is not uniformly implemented. We will talk about it later in the semester.

Bag Relational Algebra¶

Relational databases implement relational data model a bit differently.

- Relations do not have a key unless one is defined.

- Relations do not store sets of attributes if no key is defined.

A bag is a multi-set, a set that potentially contains multiple copies of the same tuple (depending on the schema).

The following is a valid table:

itemid purchase_date 1 2-21-2016 2 2-21-2016 1 2-25-2016 1 2-25-2016 It just means that item 1 is bought twice. In set semantics, this would be identical to a relation storing only 3 tuples. Not in bag semantics.

In short:

For a set, {1,2,2,3} = {1,2,3} For a bag, {1,2,2,3} <> {1,2,3}

Queries written in SQL are translated to relational algebra before they are executed. But, this version of relational is slightly different than set algebra and does not have an equivalent logic representation.

The operators take a bag of tuples as input and output a bag of tuples. We will discuss how operators change under bag semantics.

It is not possible to count values in set based relational algebra, but it is a common database operation. So, new operations are needed.

Note: In regular relational algebra, you can find if there are two tuples with a specific condition (using a join) or three tuples with a specific condition (using two joins).

It is potentially possible for any k to find if there are k tuples using regular algebra operators. But you cannot count and return how many for an unknown count query. Furthermore, the join implementation quickly becomes too expensive.

Mapping relational algebra operators to bags¶

- Selection, projection, renaming, Cartesian product and join remain the same.

- If there are duplicate tuples before the operation, they will be maintained. This is especially true for projection. Duplicates are not removed.

- Set operations are extended to bag operations as follows:

- Given a tuple t appears n times in R, m times in S

- t appears n+m times in R∪S

- t appears min(n,m) times in R∩S

- t appears min(0, n-m) times in R-S

- Given a tuple t appears n times in R, m times in S

New Operators¶

We also include a number of new operators to increase the expressive power of relational algebra.

Duplicate elimination¶

- Duplicate elimination (δ (R)) removes duplicate tuples

- Set projection now can be implemented as bag projection followed by duplicate elimination.

- All set operators can be implemented with a final duplicate elimination.

Extended projection¶

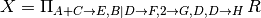

Extended projection (π (R)) projects attributes in relation R in the usual way, but

- attributes can be repeated constant values which creates a new column where each tuple has the constant value for the new column

- arithmetic and string operations involving attributes in R are allowed, and

- attributes can be renamed with an arrow in place.

- E is the sum of values for attributes A and C

- F is the concatenation of values for attributes B and D

- G is a column with a constant value of 2

- values for column D is repeated twice, the second copy is called H.

Outer join¶

Outer join (we will see this in detail for SQL): Return all tuples whether they join or not

R outer join S will return:

- all tuples in join of R and S

- all tuples in R that did not join with S

- all tuples in S that did not join with R

R left outer join S will return 1 and 2 above.

R right outer join S will return 1 and 3 above.

We can represent the outer join using logic loosely as follows (not bag semantic should hold even though we are using to represent this):

R_outer_join_S(A,B,C,D,E,F) = R(A,B,C), S(D,E,F), A=D R_outer_join_S(A,B,C,null,null,null) = R(A,B,C), NOT S(A,_,_) R_outer_join_S(null,null,null,D,E,F) = NOT R(D,_,_), S(D,E,F)

assuming a join on attributes R(A) and S(D).

Note that for statements 2 and 3, missing values from one of the relations are filled with null.

Aggregation¶

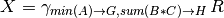

It is possible to find

- sum, min, max, avg (and other functions) of all tuples for an attribute, or

- the result of an arithmetic/string operation over the attributes for all the tuples

Example:

Note that this operation will return a single tuple as a result!

Grouping operator¶

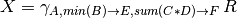

Instead of computing the aggregate for all the tuples, we can compute it for groups of tuples

- Group by attributes

- Compute aggregates for each group

- Return a single tuple for each group

Example relation R:

A B C D 1 5 2 3 2 6 0 4 2 7 2 2 3 8 1 5 3 9 3 4 We would like to compute the following aggregate:

Result of this operation is given as follows:

First we compute three groups, one for each different value of A

A B C D 1 5 2 3 A B C D 2 6 0 4 2 7 2 2 A B C D 3 8 1 5 3 9 3 4 Now, we compute the aggregates for each group. For example for A=2, min(B)=min(6,7)=6. sum(C*D)=sum(0*4+2*2)=4.

We get the following result:

A E F 1 5 6 2 6 4 3 8 17