SQL - Part 1: Basics¶

In this lecture, we will learn how to write queries in SQL.

Examples database to be used in this lecture is given in SQL here:

First a few early remarks about SQL.

Overview¶

- SQL is an industry standard language for relational databases.

- Almost all database management systems implement SQL the same, except:

- Core of the SQL standard is the same across all databases

- Advanced features may vary from database to database

- It is highly advisable to write queries that are portable from system to system: no bells or whistles unless it really gets you some strong performance gains.

- We will try to distinguish between core and special features as much as possible.

SQL as a database language¶

SQL is a full language that has many components:

Query language:

SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ...

allows you to write queries to find what is stored in databases.

DML: data manipulation language

INSERT UPDATE DELETE

allows you to change the contents of the existing tables

DDL: data definition language

CREATE DATABASE CREATE TABLE ALTER TABLE DROP TABLE

allows you to define database objects: schema, tables, indices, etc.

There are many other components to SQL, we will learn each in time.

First, query languages.

General Comments¶

A logical/declarative query language

Express what you want, not how to get it

Each SQL expression can be translated to multiple equivalent relational algebra expressions

SQL is tuple based, each statement refers to individual tuples in relations

SQL has bag semantics

Recall RDMS implementations of relations as tables do not require tables to always have a key, hence allowing the possibility of duplicate tuples

Same is true for SQL, an SQL expression may return duplicate tuples, unless they are removed explicitly.

SQL is case insensitive (though strings are case sensitive of course)

Syntax:

- All statements must end with a semi-colon!

- Strings are single quoted.

Control Flow¶

- It is best to imagine the control flow of SQL as

- From: read relations involved in the from

- Where: check for each tuple if it passes the where clause

- Select: for tuples that pass the where clause, construct the output by the projection attributes in select

- This will become very important for understanding which statements are valid.

Main Syntax: Bag Semantics and Duplicate Removal¶

Given:

SELECT course_id FROM classes WHERE semester = 'Spring' and year = 2016 ;

This is equivalent to a bag relational algebra query as follows:

Note that this query can return duplicates because there can be multiple sections for a class in a semester.

- SQL programmers need to be aware of the schema to know whether results can have duplicates or not.

If duplicates are not needed in results, then they can be explicitly removed:

SELECT DISTINCT course_id FROM classes WHERE semester = 'Spring' and year = 2016 ;

SQL - SELECT statement¶

It is a bit confusing at first, but remember: SELECT part of SQL is actually projection in relational algebra.

- SELECT is constructing a single output tuple for each tuple that passes the conditions in the WHERE clause

SELECT is extended projection:

You can rename attributes returned

You can use expressions over the attributes

You can return constants

- Optionally, you can remove duplicates using distinct (only one

DISTINCT clause in a single query)

SELECT left(name, strpos(name, ' ')) as firstname , UPPER(substring(name from strpos(name, ' ')+1)) as lastname , email , 'student' as position , email|| ' room: ' || address as contact FROM students ;

position is a new column with a fixed value, constant ‘student’

firstname is a substring of a column

constant is a concatenation of two strings

functions can be combined in complex expressions

Given SQL is a programming language, there are many utility functions that help simplify your type. You can find them here:

http://www.postgresql.org/docs/9.3/interactive/functions.html

Functions used in the SELECT statement operate on single values, not a set/bag of values: A+B, not sum(A).

AS for renaming attributes is not needed in some databases, but it is good to have to be compliant for standards.

SQL - WHERE statement¶

WHERE statement is equivalent to the selection in relational algebra.

It contains a Boolean expression over individual tuples

For each tuple produced by the FROM statement, we check whether the WHERE statement is true.

If it is true, then we produce a tuple that will be passed to the SELECT statement.

SELECT * --produce all attributes FROM meeting_times WHERE semester = 'Spring' and (year = 2014 or meetingtime > time '12:00:00') and days LIKE '%R%';

Regular Expressions using LIKE¶

You can compare a string using regular expressions, but you must use the keyword LIKE

- % stands for 0 or more characters

- _ stands for exactly 1 character

What is the difference in output?

days LIKE '%R%' days LIKE '_R' days = 'R' days = '%R%'

You can tell SQL not to treat a character as part of the regular expression by escaping it.

val like '%bc'

will match ‘abc’ and ‘a%bc’

val like '%\%bc'

will only match ‘a%bc’

You can change the escape character with the keyword ESCAPE.

like '%x%bc' ESCAPE 'x'

This will also only match ‘a%bc’.

Postgresql supports SIMILAR TO as well using more complex and SQL standard regular expressions, though it considers these regular expressions potential security hazards.

Special characters in strings¶

Strings are delimited by single quote

Escape single quote by repeating it:

SELECT 'professor''s cat' ;

Any special character needs to be escaped. The general escape character is ``.

select name || E'\n' || email from students ;

Returns values that has a newline in them.

NULL values¶

WHERE statement implements Boolean logic. However, sometimes attributes may have null values. How should they be interpreted?

NULL is a special value in SQL.

- NULL is not the same as empty string. Any data type can have NULL value.

NULL values are used to represent different things:

A value for the attribute does not exist (yet):

The grade for a course in progress does not exist.

The value exists but it is not known.

We may know that a person has a phone, but we do not know the phone number.

It is not known whether a value exists or not.

A faculty may or may not have an office yet.

Note that storing empty string for a value is asserting that its value is nothing, which is different than saying it has no value! Do not confuse the two.

Boolean Statements with NULL values¶

Given the special meaning of NULL, any comparison involving a NULL value returns UNKNOWN:

NULL = 5 evaluates to UKNOWN NULL > 5 evaluates to UKNOWN NULL LIKE '%' evaluates to UKNOWN

in this last case, any string would satisfy this condition. But, still when the value is NULL, we will return UNKNOWN.

WHERE statement will only return tuples that evaluate to True. Any tuples with UNKNOWN values are eliminated.

Boolean conditions with UNKNOWN statements need to be evaluated first:

NULL = 5 OR 4>5 EVALUATES TO UNKNOWN NULL = 5 AND 4>5 EVALUATES TO FALSE

Boolean logic with UNKNOWN VALUES:

C1 C2 C1 OR C2 C1 AND C2 NOT C2 TRUE UNKNOWN TRUE UNKNOWN UNKNOWN FALSE UNKNOWN UNKNOWN FALSE UNKNOWN UNKNOWN UNKNOWN UNKNOWN UNKNOWN UNKNOWN

Comparing NULL values¶

To check a value is NULL or not, no selection criteria will work.

create table abc (val varchar(10)) ; insert into abc values('cat'); insert into abc values('dog'); insert into abc values(null); select * from abc ; -- returns 3 tuples select * from abc where val like '%'; -- returns 2 tuples select * from abc where length(val)>=0; -- returns 2 tuples

You need to explicitly search for NULL using the keyword

IS NULLorIS NOT NULL.select * from abc where val is NULL ; -- returns 1 tuple select * from abc where val is NULL or val like '%'; -- returns all tuples

Complex expressions¶

- SQL has many functions for different data types. Any expression involving these functions are allowed.

- Some example functions:

- String operations:

||, upper, lower, position, substring, trim - Numerical operations:

+,-,*,/,%,^,! - Mathematical operations:

abs, ceil, floor, log, mod, round, sqrt - Utilities:

random, now

- String operations:

Date based data types¶

Data types:

- Date (year, month, day)

- Time of day

- Timestamp (date and time combined)

- Interval (a time duration)

Full support for complex operations on date/time data types

date '2016-01-28' + 2 = date '2016-01-30' --default assumption of day date '2016-01-28' + interval '2 day' = timestap '2016-01-30 00:00:00' date '2016-01-28' + interval '3 hours' = timestamp '2016-01-28 03:00:00' timestamp '2016-01-28 03:00:00' + interval '10 hours' = timestamp '2016-01-28 13:00:00' time '12:00:00' + interval '8 hours' = time '20:00:00' date '2016-05-19' - date '2016-01-28' = 112 -- integer number of days

Postgresql functions allow complex operations over date/time. Be careful, these functions apply to specific data types only but not necessarily do implicit type conversion:

extract(field from timestamp) --day, month, year, hour, --minute, seconds, dow select extract(year from now()); date_part ----------- 2016 (1 row)

Convert between data types:

to_char(timestamp, text) to_date(text, text) to_date('02 29 2016', 'MM DD YYYY')

You can also check whether two time intervals overlap with each other:

select (date '2016-03-01', date '2016-03-31') overlaps (date '2016-02-25', date '2016-03-04'); True select (date '2016-03-01', date '2016-03-31') overlaps (date '2016-02-25', date '2016-02-29'); False

Example: Find requirements that have been enforced for at least 1 year:

select * from requires where cast(now() as date) - enforcedsince > 365; course_id | prereq_id | isenforced | enforcedsince -----------+-----------+------------+--------------- 5 | 1 | t | 2011-01-01

FROM Clause¶

So far we have seen a single table in the FROM clause. What happens with multiple tables?

SELECT * FROM classes, courses ;

This is actually a Cartesian product of two tables. To make this a join, we must include a join condition:

SELECT * FROM classes c , courses co WHERE c.course_id = co.id

The variables c and co are aliases for the table names, especially needed if the two tables have attributes with the same name.

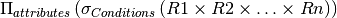

In short, a query of the form:

SELECT attributes FROM R1,R2,.., Rn WHERE Conditions

is equivalent to the relational algebra operation:

Get used to reading the above query as follows:

For each tuple in the Cartesian product R1xR2x...xRn If it satisfies the conditions in the WHERE clause Construct a tuple in the output for attributes in the SELECT clause

WHERE statement contains both join conditions and selection conditions

Example Queries¶

Return the name of faculty who taught courses both in ‘Fall’ and ‘Spring’ of 2015.

SELECT DISTINCT --multiple such courses may exist f.name FROM classes c1 , classes c2 , faculty f WHERE c1.semester = 'Fall' and c1.year = 2015 and c2.semester = 'Spring' and c2.year = 2015 and c1.instructor_id = c2.instructor_id and c1.instructor_id = f.id; -- join condition

Return id and name of all students taking a course with Professor Fogg in Spring 2016.

SELECT DISTINCT --student may be taking multiple classes s.id , s.name FROM classes c , transcript t , students s , faculty f WHERE c.course_id = t.course_id and c.semester = t.semester and c.year = t.year and c.section = t.section and t.student_id = s.id and c.instructor_id = f.id -- up to here are all join conditions and f.name like '%Fogg' and c.semester = 'Spring' and c.year = 2016 ;

Return the name of the prerequisites of the course named ‘Alternate Dimensions’.

SELECT pc.crsname FROM courses c , requires r , courses pc WHERE c.id = r.course_id and r.prereq_id = pc.id -- join conditions up to here and c.crsname = 'Alternate Dimensions';

Set and Bag Operations¶

SQL allows for SET and BAG operations:

- SET operations: UNION, INTERSECT, EXCEPT

- BAG operations: UNION ALL, INTERSECT ALL, EXCEPT ALL

The operations are over results of SQL queries:

(SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ...) UNION (SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ...)

Same as in relational algebra, the queries should be union compatible:

- Same attributes and same names (though most databases will allow same number of attributes with different names as long as the domain of attributes at each location match)

Suppose we have:

Table a1 with id values: 1,2,2,2,3,3 Table a2 with id values: 2,3,3

select * from a1 union select * from a2 ; returns 1,2,3 -- set operation select * from a1 intersect select * from a2 ; returns 2,3 select * from a1 except select * from a2 ; returns 1 select * from a1 union all select * from a2 ; returns 1,2,2,2,2,3,3,3,3 -bag union select * from a1 intersect all select * from a2 ; returns 2,3,3 -bag intersection select * from a1 except all select * from a2 ; returns 1,2,2 -bag difference

- Example: Find students who have passed ‘Advanced Spellcasting’, but

not ‘Spellcasting’. Return their name.

SELECT s.id , s.name FROM courses c , transcript t , students s WHERE c.crsname = 'Advanced Spellcasting' and c.id = t.course_id and s.id = t.student_id and t.grade is not null and t.grade <> 'I' EXCEPT SELECT s.id , s.name FROM courses c , transcript t , students s WHERE c.crsname = 'Spellcasting' and c.id = t.course_id and s.id = t.student_id and t.grade is not null and t.grade <> 'I' ;

Find faculty who never taught courses, and return their ID.

SELECT id FROM faculty EXCEPT SELECT instructor_id as id FROM classes ;

This works without renaming of the attributes, but what if you wanted to retun the name of the faculty:

SELECT id, name FROM faculty EXCEPT SELECT instructor_id FROM classes ;

This does not work, we get the error:

ERROR: each EXCEPT query must have the same number of columns LINE 3: SELECT instructor_id as id FROM classes ;

We must have the same columns for a set/bag operation. Here is how we write it.

SELECT id, name FROM faculty EXCEPT SELECT c.instructor_id, f.name FROM classes c, faculty f WHERE f.id = c.instructor_id;

Find all departments with no faculty in them or offers no majors. Return their name.

- Construct slowly, write the following in SQL:

- R1: all departments

- R2: departments with faculty

- R3: departments that offer a major

- Now we can compute (R1 EXCEPT R2) UNION (R1 EXCEPT R3)

- Construct slowly, write the following in SQL:

AGGREGATES¶

Similar to the aggregates in bag relational algebra, you can find the aggregate for a specific column or combination of columns.

Commonly used aggregates are:

min,max,avg,sum,count,stddev.An aggregate returns a single tuple (unless accompanied by other clauses like GROUP BY or FILTER).

Find total number of courses and total number of credits passed by ‘Eliot Waugh’.

SELECT count(*) as num_courses , count(t.grade) as num_passed , count(DISTINCT t.grade) as num_types_of_grade , sum(c.credits) as total_credits FROM transcript t , courses c , students s WHERE t.course_id = c.id and t.student_id = s.id and s.name = 'Eliot Waugh';

Note:

count(*)counts the total number of tuples.count(attribute)counts the total number of values for a given attribute, disregarding the NULL values.count(DISTINCT attribute)counts the total number of distinct values for a given attribute, disregarding the NULL values.

GROUP BY¶

Instead of computing the aggregates for the whole query, it is possible to compute it for a group.

- Group by multiple attributes by finding tuples that have the same values for the grouping attributes

- For each group, produce a single tuple containing grouping attributes and any agregates over the group.

- To return an attribute from a relation, you must include it in the grouping attributes.

Example: Find the total number of credits passed for each student.

SELECT s.id , s.name , count(*) as num_courses , sum(c.credits) as total_credits FROM transcript t , courses c , students s WHERE t.course_id = c.id and t.student_id = s.id and t.grade is not null and t.grade != 'I' GROUP BY s.id , s.name;

Note: we group by name to be able to return it, even though it is unique due to the primary key. If your DBMS checks for constraints at compile time, you do not have to include name. Safest thing is to include all relevant attributes.

GROUP BY - HAVING¶

Group by statement can be followed by an optional HAVING clause.

You can write conditions to eliminate gruops in the HAVING clause.

What makes sense in the HAVING clause?

Aggregates over the groups.

All other conditions should be put in the WHERE clause to reduce the size of the relation to be grouped.

Find all instructors have taught more than two courses. Return their id and name.

SELECT f.id , f.name FROM faculty f , classes c WHERE f.id = c.course_id GROUP BY f.id , f.name HAVING count(*) >= 2;

ORDER BY¶

You can order the tuples returned by the query with respect to one or more attributes.

Return the students, order with respect to year (descending) and name (ascending).

SELECT * FROM students ORDER BY year desc , name asc ;

LIMIT¶

You can limit the number of tuples returned, by the LIMIT statement, the last possible statement to add.

LIMIT makes the most sense when combined with an order by.

Find the top 3 classes in the university in terms of the number of students in them. Return their name.

SELECT c.id , c.crsname , count(*) as numstudents FROM transcript t , courses c WHERE t.course_id = c.id GROUP BY c.id , c.crsname ORDER BY numstudents DESC LIMIT 3;

FULL SQL SYNTAX¶

Now that we have seen the full SQL syntax, let’s revisit how a complex statement such as the following is executed.

SELECT A1 AS X FROM B1 WHERE C1 GROUP BY D1 HAVING E1 UNION SELECT A2 AS X FROM B2 WHERE C2 GROUP BY D2 HAVING E2 UNION SELECT A3 AS X FROM B3 WHERE C3 GROUP BY D3 HAVING E3 ORDER BY X LIMIT 10; 1. FROM B1 WHERE C1 GROUP BY D1 HAVING E1 => construct A1 2. FROM B2 WHERE C2 GROUP BY D2 HAVING E2 => construct A2 3. FROM B3 WHERE C3 GROUP BY D3 HAVING E3 => construct A3 4. TAKE UNION/APPLY SET OPERATIONS (use parantheses as needed for appropriate ordering) 5. ORDER BY (a single order per query) 6. LIMIT (a single LIMIT query)

The ordering is important. In the above query for top 3 students, we can order by a column named

numstudentsbecause ORDER BY comes after SELECT. However, we CANNOT refer to this attribute anywhere before ORDER BY (such as in HAVING).

Common Errors When Writing SQL Queries¶

Do not forget join conditions. Even if a foreign key constraint exists, you must explicitly write the join condition.

Remember the ordering of execution. The following query is is not correct, why?

SELECT student_id, count(*) as numc FROM transcript GROUP BY student_id HAVING numc > 1; ERROR: column "numc" does not exist LINE 2: GROUP BY student_id HAVING numc > 5;

Remember that aggregates only make sense after a group by statement. So, only in HAVING and SELECT.

SELECT student_id FROM transcript WHERE count(*)>1 GROUP BY student_id ; ERROR: aggregate functions are not allowed in WHERE LINE 1: SELECT student_id FROM transcript WHERE count(*)>1

You cannot return an attribute that is not part of group by.

SELECT semester FROM transcript GROUP BY student_id; ERROR: column "transcript.semester" must appear in the GROUP BY clause or be used in an aggregate function LINE 1: SELECT semester FROM transcript GROUP BY student_id;

Also think for a second to see that this query makes no sense.

You can do a selection or return an attribute that is part of group by, but be careful:

SELECT semester, count(*) FROM transcript GROUP BY semester HAVING semester = 'Fall' ;

This would not work is semester was not part of the grouping attributes.

While not technically wrong, this is an inefficient query. If you are going to do a selection on semester, you should do it in the WHERE clause. You will reduce the size of the query that needs to be processed with the remaining statements.

Here is the better version of the same query:

SELECT semester, count(*) FROM transcript WHERE semester = 'Fall' GROUP BY semester ;